Viva España

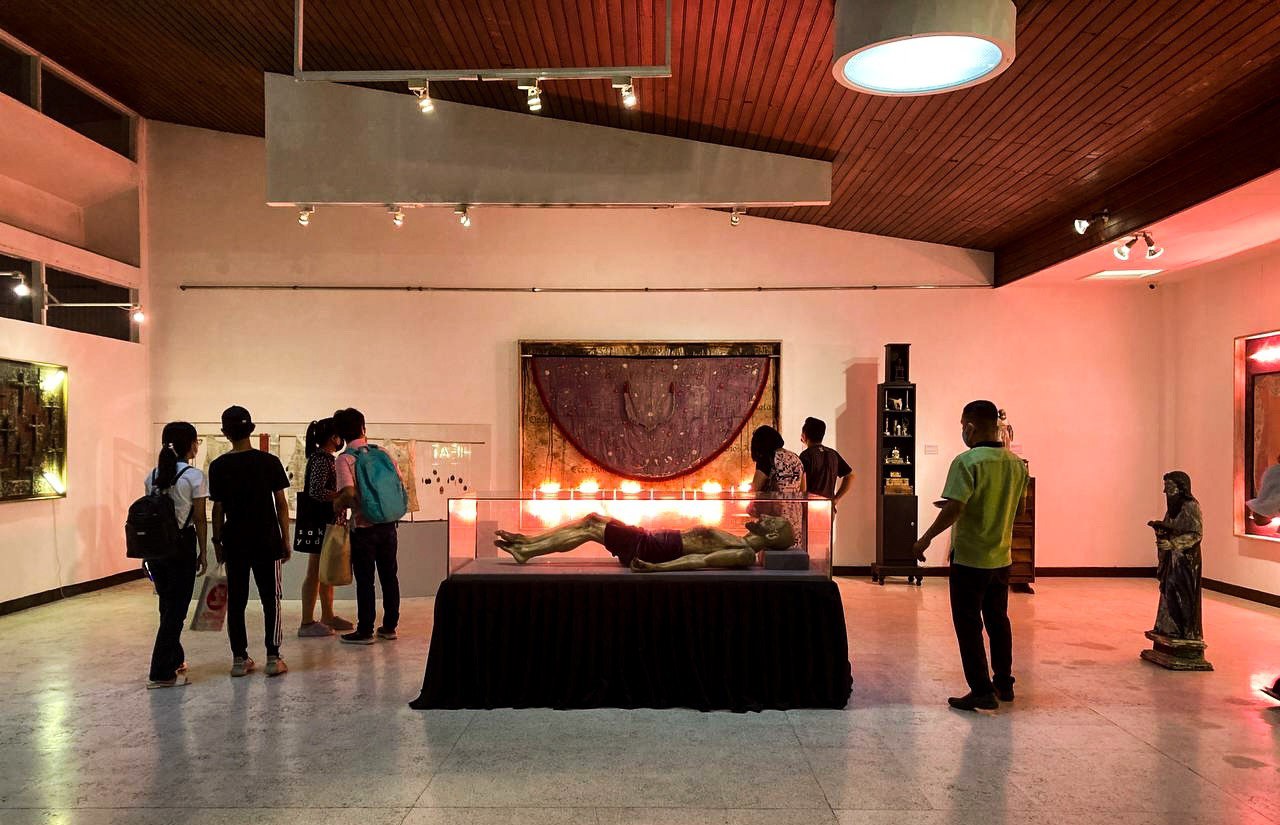

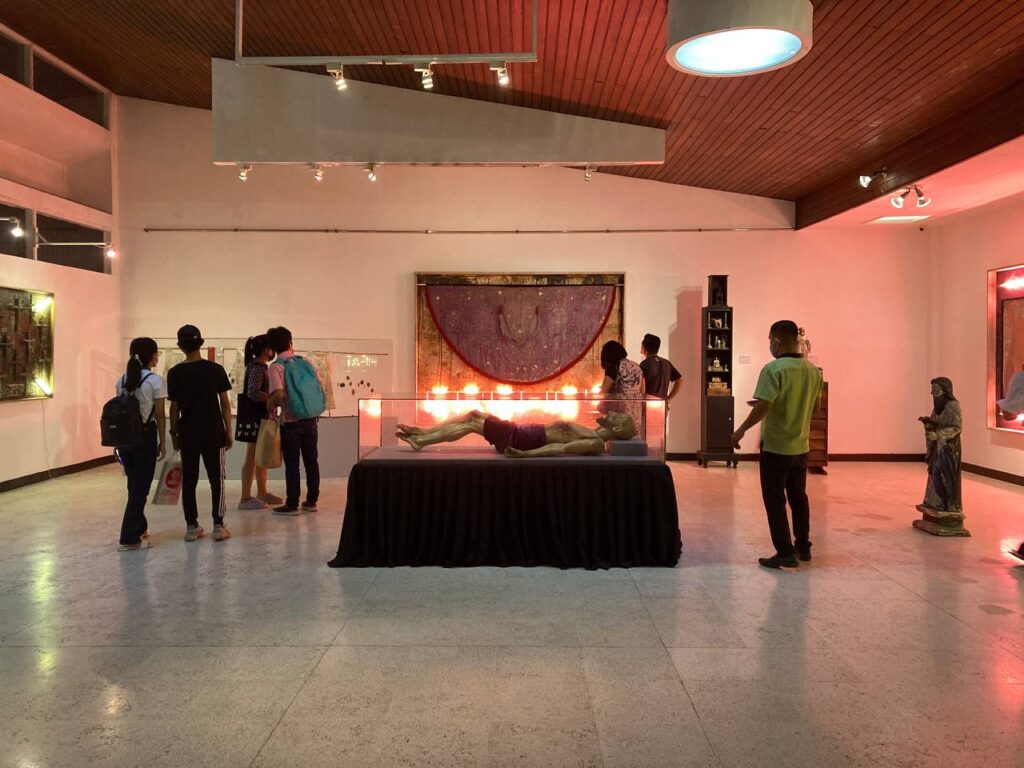

Just like an altar, there is an abundance of objects for the audience to meditate on in Norberto Roldan’s “Viva España”. But perhaps the exhibition can be viewed through three focal points that are placed in the middle of Museo Iloilo’s main gallery. First, is the Santo Entierro, the dead body of Christ enclosed in a glass case. The statue is facing the entrance with its feet pointing at the door, much like how the dead is traditionally positioned. This object is also an exercise in using artifacts to create a dialogue with the artworks and reinforce the thesis of the exhibition. The Santo Entierro being part of the collection of the Iloilo Cultural Research Foundation Inc., the organization that currently manages Museo Iloilo. The second is a temple-like structure entitled Between Salvation and Damnation. The installation is shaped almost like a base of a ziggurat, a place where people in ancient times go to attempt to connect to the sublime. During the exhibit opening, lighted candles were placed by each side of the structure. Light, being the symbol of the sacred and the divine. All this created a somewhat spiritual gathering for those who are viewing the exhibition. The third installation, The Dark Box is situated at the far end of the gallery where the audience’ viewing is most likely to end. Catholics may well recognize the installation because it is part of a ritual that has been ingrained to the followers of the faith and was introduced early in their lives — a replica of a confessional chamber covered with black cloth made of soft-lace fabric. Black often represents sin, evil and death. Most have experienced entering one at some point in their lives. In art when the theme is centered on spirituality, three is a significant number — the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost.

Surrounding the aforementioned focal points are assemblages most of which contain ephemera, scents, cosmetics, toys, etc. Each element in these assemblages are meticulously arranged inside the frame like the audience is looking at an altar bound to the wall. These artworks tap on the power of familiarity to evoke meditative experience to the audience. Some of the assemblages are encrusted with melted candle wax which seem to call to mind the notion that life is fleeting, we are all candles burning. And this similar notion is attributed to why the faithful clings to their faith.

The exhibition places the audience in an exploration of the connection of humanity to a supreme being. Roldan used the museum’s collection of santo which he placed in multiple areas of the exhibition. These saints are said to be testaments of human transcendence to the divine. They are also considered by their believers as special protectors, they cure diseases and ward off ill events. Still invoking the notion that spirituality is a cure for the soul, Roldan uses bottles of indigenous medicinal herbs resembling the bottles usually made by the Ati. He placed these bottles in a pattern resembling repetitions, much like lines of a prayer.

The title, “Viva España” is a triumphant chant in praise of the country which brought Christianity to the Philippines. At the farthest end of the exhibition is an image of the young Norberto Roldan in a spiritual ritual complete with vestments. The artist situates the personal in the social.

Long Live America

In a manner that calls to mind the processions of the Catholic Church ( via crucis,visita iglesia) the exhibitions opened in two venues with the audience transferring to the next exhibition opening after another. The other exhibition “Long Live, America” is mounted at Kri8 Art Space, —- from the other exhibition space.

Composed of huge diptychs, the exhibition is replete with images of imperialism. In the far-end of the gallery is a print of a 1900 photograph of a Spanish garrote executing a Filipino rebel while an American soldier stands guarding the condemned man. The image printed on fabric covers the gallery wall measuring more than 10 ft. Beside the image is an installation of lights that spelled out “White Love”. Curious however is that in the photo the logo of Liwayay Gawgaw, a brand of cornstarch, is imposed by the artist on the lower right portion of the photograph. Historically, Filipinos desire and seek recognition from a foreigner, which writers refer to as “white love”. In contrast the photograph shows no mercy from the foreigners given to their imperial subjects.

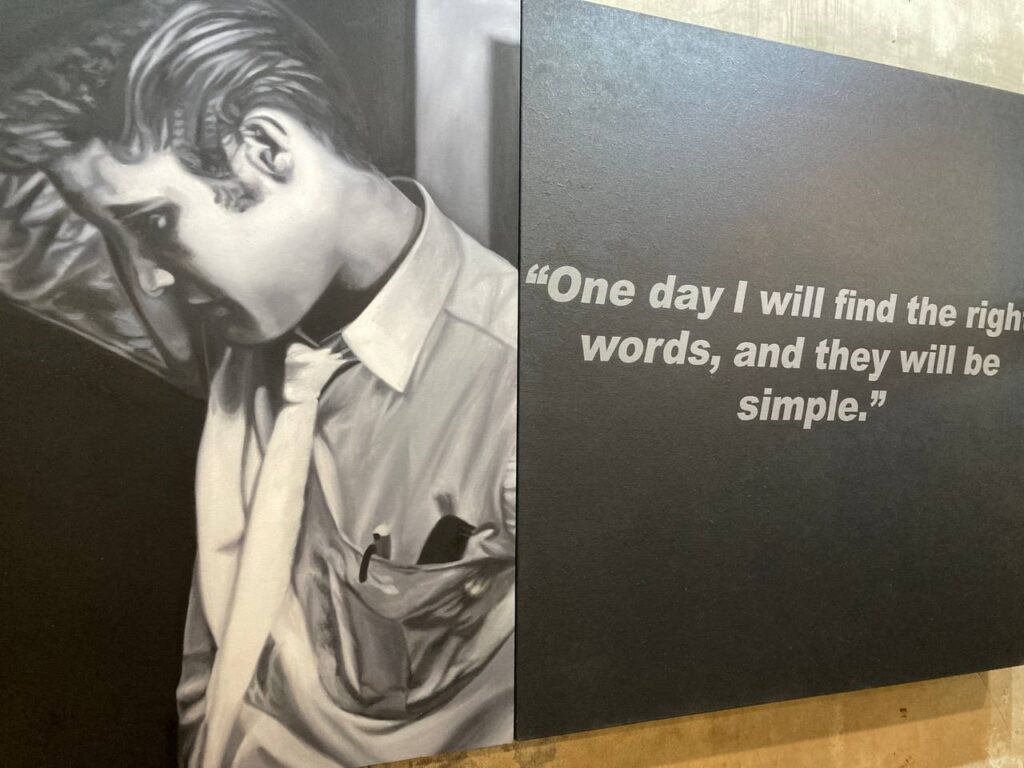

Five of the artworks featured in the exhibition are portraits of Elvis Presley, Kate Moss, Marlon Brando placed side by side with lines from their famous movies. Historian and philosopher of art, Thierry de Duve argues that “entertainment has replaced religion… but religiousness is still there”. Having seen Viva España, the audience may ruminate on the resemblance of secular idolatry to religious worship. Our devotion to these stars is comparable to the devotion to gods and goddesses with their images hanging in houses, with massively-attended gatherings in their honor, and with much of their elements being ingrained in the contemporary.

While putting these pop culture idols in the center, the other artworks in this exhibition portray the images of war. Particularly, images of bombs. The way media bombs us with images shapes the narratives of history.

Challenges and Rethinking Colonialism

Norberto Roldan’s use of materials signals the evolution of aesthetic experiences in Iloilo, a place where the pastoral scenes, the beautiful portraits, and the realistic still life are favored by both artists and the patrons. “Viva España/Long Live America” transforms the two-dimensional images confined in frames, to experiences that challenge the traditional.

Moreover, spirituality has been romanticized by Ilonggo artists as seen in paintings inside churches such as Jaro Cathedral and Sta. Ana Church in Molo, inspiring many other paintings that came after. Perhaps this is a reflection of the city as a place favored by Spain, even getting the moniker “Muy Leal Noble”.

These exhibitions come at a time when the discussions centered in colonialism are generating more reactions than before, it might be a time to rethink how we see the influence not just of religion but of western culture in general.

A longer version of this review is included in the Iloilo Art Review 2022. Get your copy below.