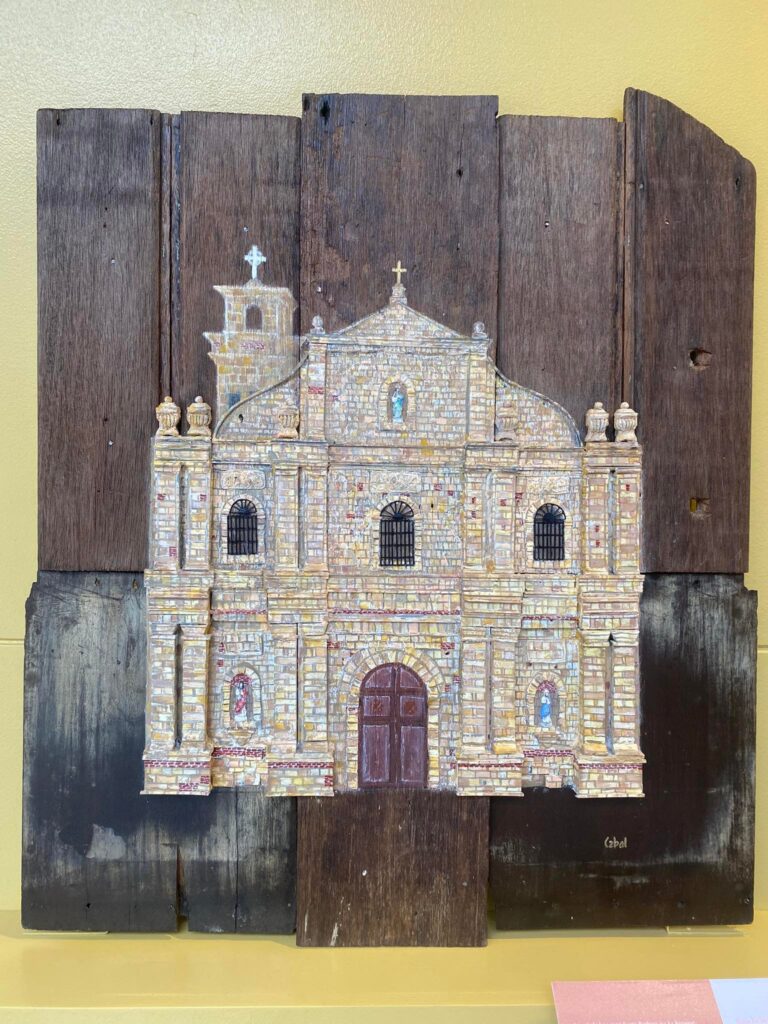

Walk through the open courtyard of the National Museum Western Visayas (former Iloilo Provincial Jail) these days and you will encounter curious miniature replicas of the churches of Panay set flat against the walls surrounding the glass-domed space. Look closely at the exhibition and you will see minute bits of mundane things assembled to create beautiful copies of these sacred structures.

Iglesia showcases a series of churches as artworks (or would the word ‘compositions’ be more apt on this instance?) of Cristhom Setubal. The exhibit takes us through a historical and cultural runway of heritage places of worship: among others, there are the old Oton church of the Immaculate Conception before it was demolished by an earthquake, the ruddy brick exterior of St. Monica’s church at Pavia, the narrow façade of Tigbauan church dedicated to St. John, the familiar ochre patina of the stones of St. Thomas de Villanova’s fortress-church of Miagao, the Gothic spires of St. Anne’s church of Molo, and of course, Jaro’s cathedral and belfry dedicated to La Candelaria. These structures are depicted on planks of wood and assembled with upcycled mixed materials ranging from computer parts to all kinds of wire, daubed with bright colors, and architecturally detailed to a meticulous extent that what meets the eye would be sharp replications of exteriors done in miniature.

There lies the irony of Setubal’s exhibit. Traditionally, theology and religiosity enshrine churches with a sanctity that sets it apart from the secular. One conventionally enters a church to pray, to attend mass or a service, to witness a wedding or a funeral, to stand godparent at a baptism or confirmation – human acts directed by a recognition and benediction of the divine. Yet rarely does one deliberately go to a place of worship to contemplate on the human condition or on the relationships that permeate and influence humanity. This paradox is subtly nuanced in the artwork; that more than the sheer bulk of sacrosanct stone (or whatever other material a church is made of), these sancta sanctorum are essentially human monuments, reflective of the church’s social function as both institution and organism: divine agent yet human congregation at the same time.

With this humanist perspective, Iglesia shifts the limelight of the acts of worship from altar or retablo to the worshippers, or more precisely, their contexts. The use of upcycled materials in the compositions invites the viewer to ‘move out’ of the structure and dwell on the details of the exterior, from the central nave out to the peripheral shell that often escapes the full panoramic view of the beholder. The hodgepodge of unwanted odds and ends evokes, if not necessarily insists, on radically altering our focus: not in the majesty of the architecture and design or the stern glances of the statuary, not in the stony insides of a church do we find imago Dei but on the humanity of the destitute and the discarded.

Through Setubal’s lens, our understandings of sacred spaces are channeled through the coming together of the mundane: the cast-off bits and pieces of everyday objects aggregate to a structural reconstruction albeit in miniature of what we consider as holy and celestial. In a visual sense, it is reimagined religiosity, rephrasing the idea of finding God in all things – these grand houses of stone rebuilt by slim pickings that mirror the social backgrounds of much of the laity who gather to worship in their naves. Beyond the vibrant hues and intricate minutiae of the artwork, the clarion message tolls clear as a bell at Angelus: in the poverty of what would have been garbage, in the last dollop of glue and glitter, there is the Divine.

References:

Compendium of the Social Doctrine of the Church (2004) Chapter 7: Economic life.

https://www.vatican.va/roman_curia/pontifical_councils/justpeace/documents/

rc_pc_justpeace_doc_20060526_compendio-dott-soc_en.html#CHAPTER%20SEVEN

Van Reken, C. P. (1999). The Church’s role in social justice. Calvin Theological Journal,

34(1999),198-202. https://www.calvin.edu/library/database/crcpi/fulltext/ctj/

68491.pdf