Editor’s Note: The full version of this article was first published on Project Iloilo in March 2016.

First Wave: Rebel Lit

A zine is a shortened term for “fanzine”. It’s a medium widely attributed to punk rock, so you could definitely see its appeal to the disenfranchised creatives, many of whom would have certainly killed for the chance to have their voices heard in a wider platform than their social circles.

“Ang plano man lang namon sang una was for us to write about things nga nakita diri namon sa Iloilo nga na-indian namon. And usually, indi lang ato ya about sa music; about guid ato sa kabilugan sa scene of Iloilo in general,” Johann Bolaño recalls.

[Our plan back then was for us to write about things we saw here in Iloilo that we didn’t like. And usually, it wasn’t even about music; it’s about the entirety of the scene of Iloilo in general.]

Bolaño and three of his peers started Undertone back in 1999, though he’s still involved in the present “scene” as part of Aftersyx. One of his partners, present-day film director Reymundo Salao, remembers where they decided to pattern the zine after when he served as layout artist for the zine.

“Guin-pattern namon on various things, sa mga magazines nga guinabasa ko sang amo ‘to nga time [We patterned it on various things, on the magazines that I was reading during that time],” Salao says. “Natural, iwat man ato daan ang mga magazines sang una diri sa Iloilo like Alternative Press, mga Rolling Stone, SPIN, amo na [Naturally, it’s rare to encounter magazines like Alternative Press, Rolling Stone, SPIN, those sorts of things in Iloilo].

Of course, Undertone wasn’t the “first” zine published in Iloilo; Bolaño and Salao credited La Postizo, said to be based out of University of the Philippines – Miag-ao, as one of their main influences for starting the zine.

For anyone lucky (or unlucky) enough to have read Undertone during its peak, you certainly couldn’t accuse them of half-assing what they set out to do, which was to hit as many targets as possible, regardless of who they offended. “Sang time nga ato, wala na ako to gabanda, pero bag-o lang ato kami natapos nga nag-untat sa sige-sige nga tukaranay. May mga iban kami nga mga articles about sa local music scene nga sakit guid ato pamatian. And iban ko nga mga friends, nairita man sa akon,” Bolaño says.

[During that time, I just came off from playing in bands and wasn’t involved in one. We had articles about the local music scene that were very difficult to listen to. Some of my friends, they were even irritated at me.]

Salao concurred, even alluding to Undertone’s content as “subversive”. “(Our content) is a bit more raw and a bit more unfiltered in the sense nga grabe (kami) manuya, grabe ang point-of-view sang una, grabe mangbira,” Salao tells Project Iloilo.

[Our content is a bit more raw and a bit more unfiltered in the sense that we don’t hold back when we insult someone, we had intense points-of-view, we criticize extremely.]

Bolaño, seemingly with fondness, recalled one of the pieces they published in Undertone that garnered them major heat within the scene: “May ara man ato nga nag-istorya to kami sa ‘Torture Chamber’ namon nga column nga daw peak ato sang street party-street party diri sa Iloilo. Tapos, daw guin-question namon ang (pagpati nga) ma-street party kamo, pero no different man nga guina-provide nga bag-o. Daw same man guihapon nga butang nga guina-ubra ninyo sa sulod sang bar niyo kag guindala niyo lang sa guwa, which is okey guid man, amo guid man tani,” he narrates.

[Back then, we told a story on our ‘Torture Chamber’ column when it was during the peak of street parties here in Iloilo. We questioned the thinking that you’re going to hold a street party, but it’s no different and you’re not providing something new. It’s still the same thing where you hold it inside your bar and then moved it outside, which is just okay, and was the point.]

He then doubled down on what his real issue with the whole thing was. “Pero amo na bala tani: nag-ilog na lang kamo sa konsepto, tarungon ninyo man kay kahuluya. Kung may makakita be nga mga bisita halin sa iban nga mga lugar—let’s say, Manila, tapos makadto diri—makita nila nga, ‘Ay, amo ini ang street party sa Iloilo? Daw kabitin or kasala.’ Kahuluya.”

[It’s like this: you followed the concept, so do it properly because it’s shameful. What if someone from another place—let’s say Manila—sees it and says, ‘Is this what a street party in Iloilo is? It looks lacking or wrong.’ Shameful.]

Second Wave: Alternative Iloilo

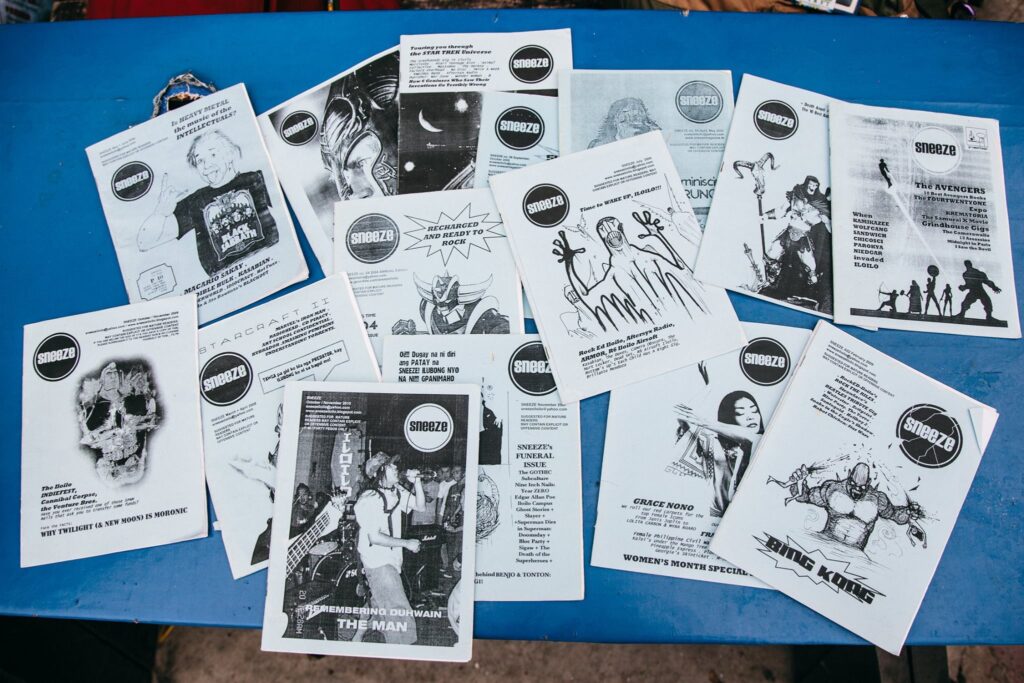

Even when Salao eventually veered away from Undertone to start another zine called Sneeze in 2004 because he thought they needed to go “mainstream” (his words) if they would have a hope of surviving, he still aimed it to be different than what was the norm in Iloilo’s publishing during those times. Along with writings about the Jaro belfry and profiles on Ilongga heroine Teresa Magbanua, his zine tried to spotlight artists it could find within the staff’s cliques—musicians, painters, skaters, photographers, the entire lot. And, precluding the mainstream pop culture landscape by a good ten years, they’re one of the few local publications I could remember that trumpeted a geek-friendly feel.

“Iwat pa ang magazine, iwat pa ang mga balita about music and culture and art—I think amo na. It’s the… need for alternative media. Indi ang media nga ma-get mo lang sa mainstream,” Salao tells us.

[Magazines were rare back then, even rarer were news about music and culture and art—I think it’s that reason. It’s the… need for alternative media. Not the media that you can only get from the mainstream.]

Sure, Sneeze tried to make itself more palatable to local advertisers, but make no mistake: it was still a publication made by misfits for their fellow Ilonggo misfits. Of course, it also helped that the 2000s “rakista” era was in full swing back then: “Sang time nga to… damo man nga mga gaginuwa man nga mga local nga bands. I mean, sang time sang Undertone sang una, damo na guid man to sang bands. Pero paguwa sang Sneeze, medyo nagdugang na guid.” Salao postulates.

[During that time, there were a lot of local bands that came out. I mean, there were bands during Undertone’s time. But when Sneeze came out, there were just more of them.]

Hard to argue with that notion: that was the time when local bands like Point Click Kill and Diet of Wormz were enjoying cult-ish, national recognition. And Sneeze, as it turned out, was the scene vanguard by default.

If you even thought Sneeze watered down Undertone’s dissident spirit, then it certainly wasn’t obvious. The staff not only centered their crosshairs against what it saw as the “hangag” of Iloilo (almost every Sneeze editorial I read contained that descriptor, so make of that what you will), they also supplemented it with a healthy skewering of global pop cultural touchstones of the time like the ‘Twilight’ and Michael Bay’s ‘Tranformers’ movie series—yep, the kinds of stuff hardcore geeks were supposed to be angry about in the mid-‘2000s.

Undertone eventually transitioned into another zine called ‘Talk Sheet’ before it folded; Sneeze, however, was enjoying semi-regular circulation to the point that stocks of its back issues were always available in magazine stands at major malls within the city. In 2012, Salao was eventually able to transform the brand into a proper magazine—colored pictures, snazzy layouts, and all the bells and whistles that come along with it.

The problem? They “relaunched” the newly formatted Sneeze in 2012—a time when Philippine interest in glossies were beginning to decline. And the thing is, many of the people involved in the zine were even keenly aware of it.

Third Wave: A Painful Transition

Being uncompromising rarely pays. Or, at least, that’s what I got from Bolaño when he recalled about the death of Undertone.

“Gaplano na kami nga dakuon na siya nga daw magazine na nga size... So, since dako nga money ang involved, masulod na ang marketing. And I admit, kung sigihun namon ang format namon nga ato, indi ka guid makakuha advertisers nga maayo,” he explains.

[We were planning to upgrade Undertone to be more of a real magazine. So, since there would be a lot of money involved, this was where marketing would come in. And I admit, if we continued with that format, we could not get any good advertisers.]

Sneeze’s transition to a proper magazine format also came at great cost: “Nangayo ko ato bulig from friends. For a time temporarily, indi na to ako ang naging owner (sang Sneeze); bale shared ownership guid with other people. Pero wala man ato nag-sige kay daw medyo indi siya feasible in the end,” he says.

[I asked help from friends. For a time temporarily, I wasn’t the owner of Sneeze; it was a shared ownership with other people. But it didn’t last since it wasn’t feasible in the end.]

Salao maintained he loved his time running Sneeze, but the experiences he gained from it were largely “negative”, as he put it. “For example, ang na-learn ko ya is that indi ka magsalig sa Ilonggo market nga mag-shell out sang money (for a local product),” he exclaims with a laugh.

[For example, what I learned was that you don’t have to trust the Ilonggo market to shell out money for a local product.]

Why does this sound so familiar? Oh, right.

However, Bolaño argued that the zeitgeist for a zine to exist just isn’t there today. “Ara na ang technology mo. Ang mga newspapers kag mga magazines gani, gakapatay, guina-digital na nga format,” he muses. “Although kung sa amon, kung may ara gusto mag-ubra sang zine, puwede man na guro.”

[The technology is there. The newspapers and even the magazines, they’re dying and being transformed into digital formats. Although for us, when someone wants to make a zine, it’s probably possible.]

Well, someone did make a zine, though it’s not one that either Bolaño or Salao may had foreseen. Kristine Buenavista* and visual artist Marrz Capanang started Kubyal, though it’s not because they needed a platform to rail against something. As Buenavista put it in an email interview, they wanted to make a medium containing “positive reads”.

“We met a really awesome couple when we traveled in Siquijor Island last February 2014. They were from Davao City. We traveled a bit together, shared stories and visions and we (Marrz and I) were so inspired by their projects,” Buenavista wrote. “They craft zines and give them away – to educate people. We thought it would be awesome to do something like that in Iloilo.”

Surprisingly, they didn’t draw upon any specific influence when they started Kubyal. “We just wanted to follow our compass,” Buenavista wrote. Referencing the myopic effects of what are arguably the “echo chambers” of social media have today, she explains, “We get all the negative updates everywhere nowadays, we attempted to compile writings and stories that feel lighter yet somehow powerful.”

Buenavista and Capanang were able to secure donations for Kubyal’s first issue from friends both in and out of the Philippines. Printed on the right side of the masthead was, “Please share this zine among friends or strangers.” Regardless, Buenavista admitted that they needed to do some major organizing if they’d ever plan on releasing future issues. “One thing we need to improve on is the delegation of responsibility when it comes to the printing and distributing,” she writes.

You really have to wonder why anyone would want to take on such a thankless job of running what is essentially a small-scale version of a self-funded magazine. Well, Buenavista has this to say: “I believe there is more romanticism in zines.”

Can’t argue with that.

The Fourth Wave: The New DIY

Zines may still have that pragmatic quality to them that really isn’t afforded by modern tech. Buenavista, is more concerned with its straightforward process: “(Zines) are handcrafted…they can get faded, torn, passed on to others by hands…and hmmm this I love the most, there is something so raw in them,” she writes.

Besides, it’s not like the people involved with these zines have completely moved on doing “normal” things: Bolaño’s and his cohorts tireless hustling for Aftersyx resulted in the collective releasing a new record for 2016, as well as being included in an international electronic music compilation; Salao’s first full-length film, ‘Ugayong’ premiered at the last CineKasimanwa; and Buenavista, along with Capanang and a few of their friends, are currently involved in several non-profit projects.

Creative people will always find ways to express themselves, and zines—much like any medium that have preceded and will come after it—are no different. I’ll be the first one to admit that Project Iloilo may not even exist if it weren’t for outfits like La Postizo, Undertone, Sneeze, and all the self-published zines that we may not have known about. They documented more than just the prevailing culture of their time; they created spaces where originality was a trait that wasn’t just highly encouraged, but often fought for. It just got a little easier to do so today because…. Well, we do have the Internet.

Likewise, it seems like Iloilo City is inching towards a new Golden Age. Sneeze, for all its snotty brashness, was oddly optimistic about Ilonggo culture in one of its non-angry editorials:

“What Iloilo needs is not to expand structurally. But culturally. Notice how IMBALANCED Iloilo is. There is an overflowing community and power of Pop Culture. Pop Culture that is very much associated with commercial culture. And commercial culture is controlled by powers interested in profit.”

Hey, we may be already getting there.

Photos by Christian Lozanes