Behind the paintbrush and the loom

In recent years, the cultural scene of the Province of Aklan has experienced numerous transformations – owing to the commitment and tireless efforts of Akeanon writers, historians, artists, and cultural workers. Akeanon identity is continuously being woven into a fabric that transcends the eco-tourism cliché of island life in Boracay and the annual Ati-atihan festival. Tangible and intangible forms of Akeanon cultural heritage and perspectives on local history that were almost left in obscurity due to the economic hype in the paradise island these past decades are now given attention by the public and the local government. Among these cultural movements that sought to reimagine Akeanon identity is the revival of the traditional piña weaving industry in Aklan which gained momentum in the mid-1980s. And hardly can the story of the revival of this industry be discussed without mentioning the life, art, innovations, and advocacy of Anna India Dela Cruz Legaspi.

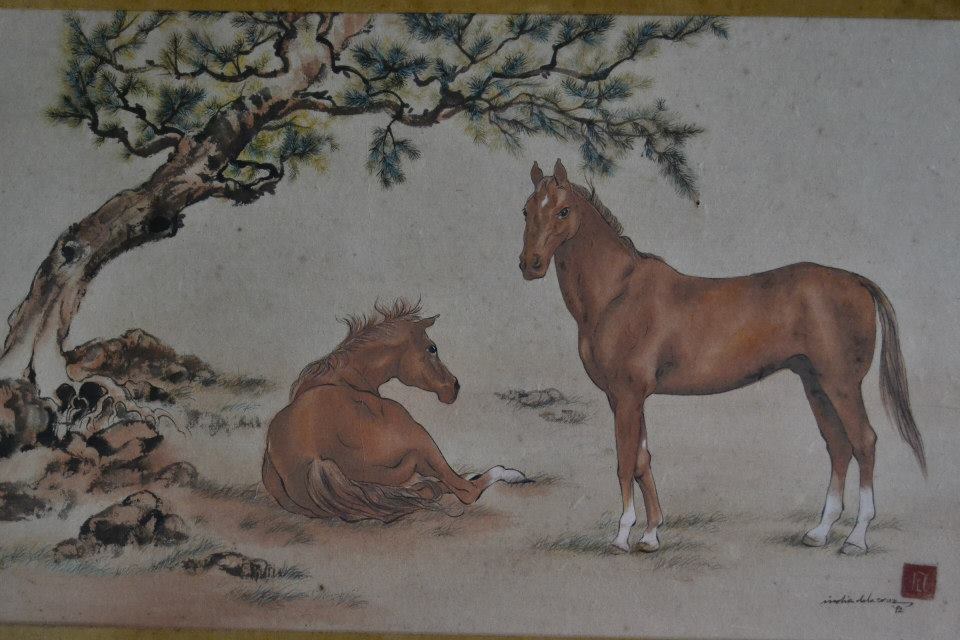

One can still find Nay India at her old house along L. Barrios Street, at the heart of Kalibo, with a sala that is typical of an artist’s abode – full of art materials, books, paintings, and because of her advocacy, piña and abaca textiles. She is a soft-spoken person yet very expressive, especially when it comes to the subject of her artworks and of piña weaving. She is known for her paintings which use traditional textiles such as piña and abaca as canvas, and for developing the piña seda which is a textile blend of pure piña mixed with silk. Her notable works and contributions towards promoting traditional piña weaving brought her to Europe, the United States, and in a number of Southeast Asian countries. She was also invited as a resource person on piña weaving at the Osaka International University in Japan. In a program that sought to showcase the artistry and diversity of indigenous weaving traditions (which includes both textiles, embroidery, and traditional weaving processes) of the various ethnolinguistic groups in the country, then-senator Loren Legarda, in 2015, initiated a program called Hibla ng Lahing Filipino – in which Nay India received recognition at the Exposicion Itinerante Hibla ng Lahing Filipino in Madrid, Spain, for developing the piña seda. A series of her paintings on piña cloth portraying the tedious step-by-step process of producing the piña textile was once embedded in the pillars inside the lobby of the Development Bank of the Philippines (DBP) in Kalibo; and currently, another series of the same subject is displayed at the new building of the Sangguniang Panlalawigan of Aklan.

Early interest in the arts

Nay India’s interest in the visual arts started early, as she recounts that she was already fond of drawing during her childhood. She also added that the majority of her relatives in the Dela Cruz side of the family were also inclined in the arts, being artisans and weavers and that her father – the late Manuel Aguirre Dela Cruz, a World War II veteran, lawyer, and grandson of one of the 19 martyrs of Aklan – also had an influential part in Nay India’s journey as an artist. Moving to Manila in 1953, Nay India continued her passion for the arts and became an artist for their school organ at St. Paul College, Quezon City, during her high school years. It was, however, after her secondary education that Nay India would finally chart her path as an artist. Though originally her father wanted her to pursue a medical course at the University of Santo Tomas, an unexpected and rather humorous turn of events would change everything for Nay India. When asked of this pivotal event that led her to pursue the arts, Nay India recalled vividly the time she was familiarizing herself with the College of Medicine building at the university and, by some chance, opened a door that led to a laboratory full of cadavers. In the horror of what she saw, she ran back home to her father and declared that she would not continue her course in medicine and would instead take up Fine Arts. The frightened would-be medical student then found herself taking up Fine Arts, majoring in Advertising Arts, at the same university. And so, thanks to a room full of cadavers, the Akeanon people had gained a committed artist and cultural advocate.

On using piña textile as canvas

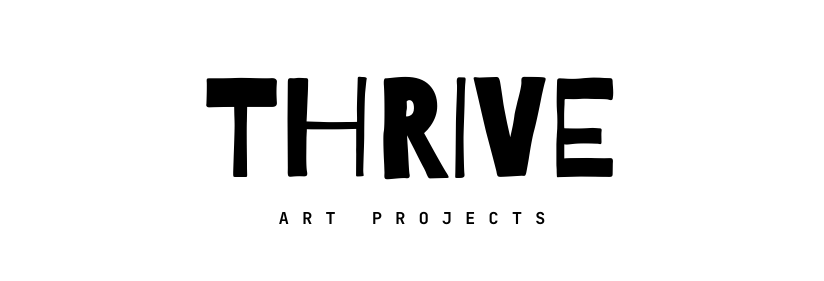

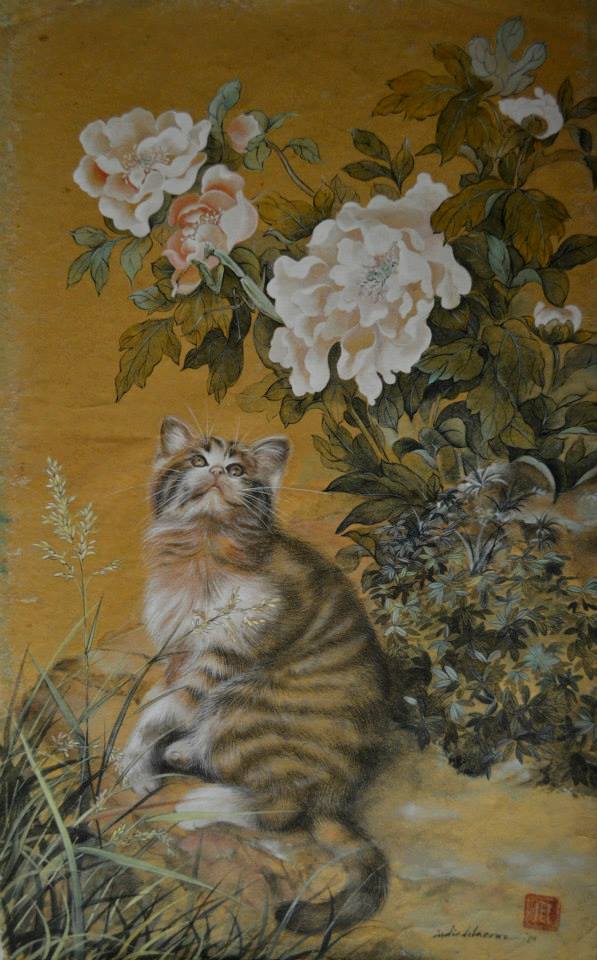

Nay India’s use of piña cloth or fabric in her paintings and her advocacy for the industry started much later, while she was already working as an artist at United Laboratories, Inc. Some of her contemporaries at that time were studying Chinese painting; of which she also developed an interest for, and decided to study the art for 4 years. During this special study, she was under the mentorship of Professor Chen Bing Sun who introduced her to oriental art, the classical style of Chinese painting. Aside from classical Chinese painting, Nay India also studied contemporary Chinese painting or the Lingnan style under Hau Chiok. Nay India differentiates the two styles, stating that the classical style is “more on details”, while the contemporary or Lingnan style “has bold strokes and bright colors”.

In her Chinese paintings, Nay India would use silk imported from China as her canvas. In seeing that she was painting on this material, her grandmother, Presca Meñez Aguirre, who was herself a former manug haboe (traditional weaver), brought out her last 10 meter-long piña cloth which she had kept inside a ba-oe (a chest) from the time they moved to Manila, telling Nay India that someday she would make use of the traditional piña cloth in her artworks. It was at that time, after seeing the fineness of the textile, that Nay India developed the idea of using the piña cloth as a canvas for her paintings.

“Nakita ko, nga manami ta gali ru piña, so dikaron ako nag piniino nga, ham-an it indi ko gamiton as canvas ru piña instead of silk na imported from China, hay may manami man nga local textile nga puwede kong i-gamiton as canvas”

“I saw that the piña [cloth] was good, so that’s when I realized that why should I not use piña [cloth] as a canvas instead of silk imported from China, when there is another local textile that I can use as a canvas.”

By making piña cloth as a medium for her artworks, Nay India has proven that the piña cloth of Aklan, apart from being a material for clothing, and though delicate in appearance, can be both versatile and strong.

Textile blends originally developed by Nay India

Aside from her paintings on piña cloth, which were often displayed as centerpieces during the exhibits and trade fairs for handicrafts of the Department of Trade and Industry (DTI); Nay India, upon the recommendation of a merchandizer from Rustan’s, also made use of traditional textiles by producing hand-painted functional items such as doilies, placemats, and runners. After establishing a business centered on art and crafts using these traditional textiles, Nay India saw the need to encourage the production of piña textiles which were strictly sourced from the red Spanish pineapple variety, whose fibers from its leaves have been used in the practice of handloom weaving in Aklan for centuries. The task of reviving the tradition of weaving in the province became then her advocacy. She did not, however, limit herself on the traditional piña cloth; as she went on to develop a number of textile blends such as the piña seda, banana seda, cotton and piña, abaca and silk, and poly-hemp or polyester and abaca. The piña seda, in particular, helped revolutionize and support the piña weaving industry in Aklan since the pure piña fabric called Liniwan takes a long time to produce – with a skilled worker taking one day to produce just about ¼ meters of the fibers; whereas, the piña seda takes up less time, with a single worker able to produce 2 meters of the fiber a day. The reason, according to Nay India, is that “it uses silk for its warp and piña for its weft”, which subsequently makes the production of the fabric much faster, albeit sacrificing its quality.

Despite these textile blends being her original innovations, she did not bother to register these textile developments with the IPO (Intellectual Property Office); as apart from the unfortunately lengthy, bureaucratic, and oftentimes costly nature of procuring these rights, Nay India saw it as her contribution, her own personal way of helping the tradition of weaving to flourish in Aklan. After incorporating the various textile blends that she had developed, the weaving industry in Aklan, particularly that in Kalibo, saw an increase in its workforce – as the local industry began to cater to both local needs and global market demand.

The development of these textile blends also created a mark in the fashion industry. Fashion designers such Patis Tesoro, Dita Sandico Ong, Barge Ramos, and Armando Giron took inspiration from much of Nay India’s works on traditional textiles and fused them into their clothing designs. The former fashion designer and now Benedictine monk Dom Martin Hizon-Gomez, OSB, who is well-known for his use of traditional textiles for church vestments also incorporated Nay India’s textile blends and even featured most of Nay India’s textile developments in his book, “Worship and Weave”.

Subject of artworks

When asked about the usual subjects of her paintings, Nay India says that she draws inspiration mostly from nature and still life such as flowers, animals, bamboo, and sceneries in the locality. At times, she added, her composition takes one element and incorporates or compliments it with another element, such as, for example, a separate flower which is integrated into a scene containing other flowers or ornamental plants.

Challenges to the industry

As with any endeavor to enrich the culture and the arts of a particular locality, there are always a great many challenges and obstacles that are to be faced. The challenges of the traditional weaving industry in Aklan, as Nay India would put it, is “a roller coaster ride, a series of ups, plateaus, and regressions”. An almost recurring issue to every effort of preserving traditional skills and practices such as weaving is the aging of the bearers of the tradition. Due to the old age of most of the traditional weavers in Aklan and with the youth losing interest in inheriting or learning these traditional processes, Nay India stresses the need to conduct proper training to transfer the skills and knowledge of traditional weaving to the next generations. The supply of the piña fibers is also another issue, as the ability to produce high-quality piña textiles relies on the farming of red Spanish pineapples and of the tedious process of knotting the individual fibers which require great skill and patience.

Added to these problems of supply and production, are issues on intellectual property and the government policies which at times, though indirect, prove to be detrimental to the development of local industries. Nay India’s innovations of textile blends have also been copied and reproduced by various groups and individuals without acknowledging its origin, and attempts were made by foreign companies to mechanize the production of the piña cloth. These attempts to mechanize the production of the textile have failed, primarily due to the fineness of the individual fibers from the red Spanish pineapple. She further points out that the piña fibers, which need to be knotted by hand, cannot be mechanized, not unless it is “cottoned” or cut into small pieces and mixed with cotton or synthetic materials like polyester. On the other hand, government-led efforts, if ill-conceived and lacking in proper consultation, also become threats to local traditional industries like piña weaving. By focusing on mass production instead of preserving product quality and preserving traditional skills/processes, some efforts have led to low-quality and substandard products, such as with the move to substitute the red Spanish pineapple with the Hawaiian pineapple for the source of the fibers, which resulted to a fabric that is easily torn due to the latter’s fibers not being ideal for traditional weaving.

The mission continues

Despite the unethical copying and reproduction of the textile blends by the individual or collective entities outside of the province and the oftentimes problematic approach of government institutions with regards to local industries, Nay India continues to innovate on the traditional textiles of Aklan – experimenting on new blends, developing functional products, and of course, infusing her art into the textiles. Due to her expertise and knowledge of the textiles and of the weaving process, Nay India took part in the development of the TESDA Competency Standards for the NCII (National Competency II) on upright handloom weaving, in partnership with the NCCA (National Commission for Culture and the Arts), PTRI (Philippine Textile Research Institute), and the weavers themselves. With this collaboration, handloom weaving is now institutionalized as a TESDA course, wherein local weavers, with their expertise in the traditional crafts, are being recognized as master weavers.

Nay India’s artworks and her advocacy on traditional weaving show us how tradition and innovation can be negotiated, and that how the practice of age-old traditions are needed to be institutionalized and continuously transformed for it to flourish. As for young and aspiring Akeanon artists, Nay India imparts an important lesson on tradition and the prospects of traditional crafts:

“If you want to show the Akeanon identity then you go into traditional, traditional crafts, but develop it into something na artistic, innovative, para makilala ka at the same time makilala ang province mo…so ang ibig sabihin niyan is you cannot go wrong if you put your art with tradition, if you incorporate or blend your art with your traditions. Craft traditions need not be stagnant. While maintaining its practices, creative innovations must be part of its development for contemporary use. The repeated practices of today become the traditions of the future. And by blending modern ideas with traditional and existing concepts, our culture and traditions will live on. ”