I remember a conversation I had with a fellow artist a long time ago. The artist expressed concern after observing a huge difference between an interpretation of their painting by an art critic and what they thought was the actual meaning of the work. As an artist myself who dabbles in some art writing in my spare time, I tried my best at that time to mediate the opposing perspectives of the author of the work (the artist) and that of the critic, using random internet quotes and obscure lines of “freedom of expression” from the Constitution to support my stand. What I lacked at that time was a solid list of theories that could back my argument. I believe I still have a lot of “blind spots” or “gaps” in my knowledge of the different theories but I’ll try my best using my access to Google and free online libraries.

Authorial Intent

In my observation, many artists, and some who write about art, come from the position of strong “authorial intent” which posits that the artist or creator of an art object embeds or encodes the meaning or intention in the artwork itself. Strong proponents of this view believe that the “meaning of the work is dependent on the authorial intent (what the creator intended for the artwork to mean).

This is how art criticism was written in the past. The interpretation of an artwork leaned towards understanding the artist and their context to arrive at the “true” meaning of the work. An extreme example of this view is from C.S. Lewis who in the book “An Experiment in Criticism” wrote “The first demand any work of art makes upon us is surrender. Look. Listen. Receive. Get yourself out of the way.” Another proponent of this position is E.D. Hirsch, who wrote in the book Validity in Interpretation (1967) “the sensible belief that a text means what its author meant.”

Evolution from Authorial Intent

The challenge with authorial intent is that a viewer needs more than just looking at the art object – the viewer or audience will have to dig deeper, acquire private knowledge about the artist and their process, and know other contextual information that existed outside of the work. Writers argue that outside knowledge “might be interesting for historians, but it is irrelevant when judging the work for itself.”

As criticism evolved and writers embraced the ideas of ‘intertextuality’ by thinkers like Bakhtin, and the ‘death of the author’ by Barthes and Foucault, it is thought that it would be impossible to understand and comprehend entirely what compelled a creator to make a work of art. In ideas of ‘post-structuralists’ like Jacques Derrida, “the author’s intentions were unknowable and irrelevant to the constantly shifting interpretations produced by readers.”

“Death of the Author” is a concept developed by literary theorist Roland Barthes, which suggests that the author’s role in determining the meaning of a work is diminished. Instead, the focus shifts to the reader’s interpretation, allowing them to generate new meanings and insights. Barthes “argued that once a work was published, it became disconnected from the author’s intentions and open to perpetual re-interpretation by successive readers across different contexts.”

The focus of reading a work of art shifted from the historical and biographical context and moved towards “how a work creates meaning as an entity to itself”. One of the most extreme examples of writers against authorial intent comes from Art Critic Jerry Saltz who said “Artists, you do not own the meaning of your own work. If you say your works are about scrambled eggs and I see it as sunflowers, for me, your work is a sunflower.”

The Artist’s Oeuvre Vis-à-vis Curatorial Notes

In the art world and art institutions, the contemporary practice of understanding the work of art is, in many cases, in the context of an exhibition or an art show in art world institutions of museums, galleries, and art spaces. These exhibitions include the many art objects and curatorial or exhibition notes that may be essential in assisting the viewer to make sense of the artworks. In contemporary practices, the curator may or may not have an intervention in the creation of the pieces, and the curatorial notes, as a result, may or may not interpret close to the authorial intent of the individual pieces. The question remains if the curatorial notes in themselves can fully explain the individual works included in the exhibition if they create new meaning from an anti-intentionalist approach as they create new text, or if they provide a middle ground.

Since the curatorial or exhibition notes are written by a qualified audience such as a curator, arts manager, or any of the individuals operating under the umbrella term of “cultural worker”, perhaps it can provide a moderated middle path between ‘actual intentionalism of Authorial Intent’ and ‘anti-intentionalism’. Writers may call this ‘Hypothetical Intentionalism’ which is a strategy used in interpretation that navigates the assumption of an author or artist’s actual intent, and then eventually disregards intent altogether, to produce the best hypothesis of intent as understood by a qualified audience. This approach prioritizes the perspective of an intended or ideal audience, which employs public knowledge and context to infer the author’s intentions.

To compare the extremes of interpretations, the Authorial Intent exemplified by the likes of C.S. Lewis who wanted the viewer to “surrender” to the artwork, and the ‘anti-intentionalist’ pronouncements of Jerry Saltz who interprets “scrambled eggs as sunflowers”, we have more institutional writers like Terry Barrett who said, “the meaning of a work of art is not limited to the meaning the artist had in mind when making the work; it can mean more or less or something different than the artist intended the work to mean.” He also wrote “When writing or telling about what we see and what we experience in the presence of an artwork, we build meaning; we do not merely report it”.

Art Making and Interpretation Is Dynamic

The artistic act becomes dynamic in such a way that when a work is presented to the public it produces countless “views” which becomes an instance of the original artistic act. Each instance is an opportunity for the “viewer” to have his or her own interpretation – some in thought, some in writing, and in others, inspired to create a work of art.

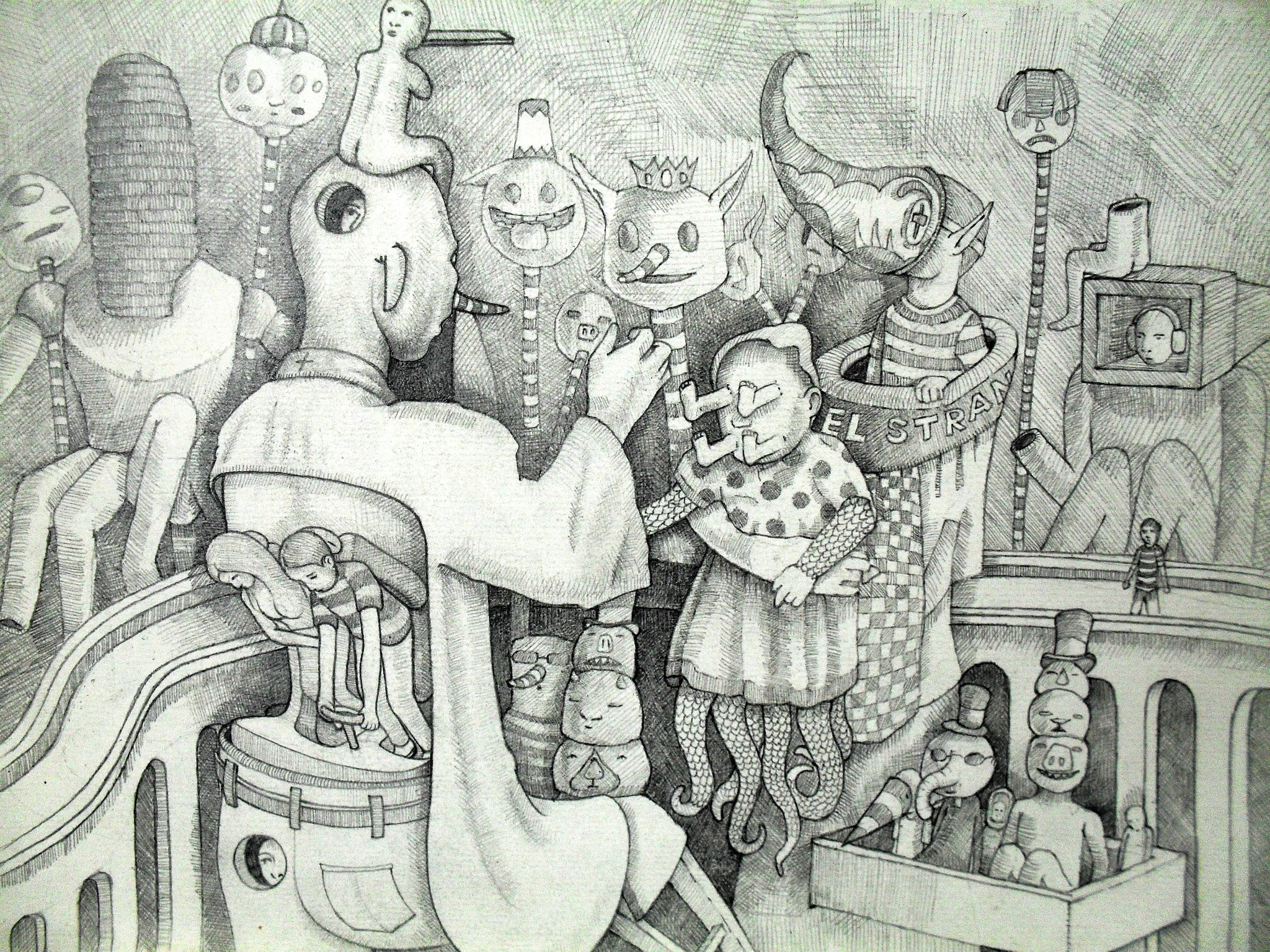

The artwork featured in this article is an old study for a painting I have yet to make. I chose this artwork as I feel it would challenge the audience to imbue it with meaning.

Artist Log is the column of our founder, Kristoffer Brasileño, where he shares insights about his art practice.