An approach to the exhibit

I first came across the term “tayog-tayog” when I was studying in Iloilo City. When someone tells an “out of this world” story or claim, that person is “tayog-tayog mag-isip/mag-istorya.” A person who shares these “tayog-tayog” stories and ideas is often dismissed and laughed at in peer groups. However, the exhibit “Tayog-tayog: The Ilonggo Imagination” sought to present a somewhat post-structural take on the term by emphasizing the richness of the Ilonggo imagination and by celebrating what mainstream society would see as a hint of madness.

While I believe that this is the message of the exhibit’s theme, we are nevertheless confronted by how the various artists perceive the characteristic of “tayog-tayog.” As in any critical review or reflection, we have to start with questions: are these imaginings purely taken from the depths of the subconscious, as in dreams, or from emotions that arise from memories of someone, of a thing, or place? Or are these imaginings curated by a certain body of knowledge whose possible sources also merits our attention?

On the opposite axis, we can also try to distinguish between the personal and the collective imaginings. The source and proprietorship of these imaginings can be a guide in exploring some of the noteworthy works in the “tayog-tayog” exhibit. This also to say that there is no one absolute Ilonggo imagination, as the imaginings of these artists are almost always hinged to their own distinct biographies – their social milieu, socio-economic status, ideology or faith, and lived experiences as Ilonggos.

Of the barrio, faith, and death in the cities

The following, I believe, are personal experiences derived from familiar collective practices and knowledge: Kristoffer Brasileño’s “Hutik sa Kagab-ihon,” Alex Ordoyo’s “The story of Candelaria,” Kyle Sarte’s “La-Familia Indio,” and Rolando Manuel Jucar’s “Tigbaliw.”

Brasileño incorporates the elements of storytelling, the Filipina, and textiles. From folktales, legends, to aswang stories, these narratives are usually told in the evening by our mothers or, in middle-class families, by the children’s yaya. Even a child from a well-to-do Chinese-Mestizo family such as Jose Rizal would come to remember such stories from his beloved hometown of Calamba. As storytellers they, too, are cultural bearers of our oral traditions much like the epic chanters of our indigenous peoples. Their individual stories might initially be seen as loose and entangled narratives; however, if viewed as a social phenomena (storytelling at night) these entangled narratives form a tapestry that is part of a rural mentalite. From their “tayog-tayog” stories hold the memories of the rural barrio and as such brings out a sense of nostalgia for those transplanted into the urban-regional centers such as Iloilo City.

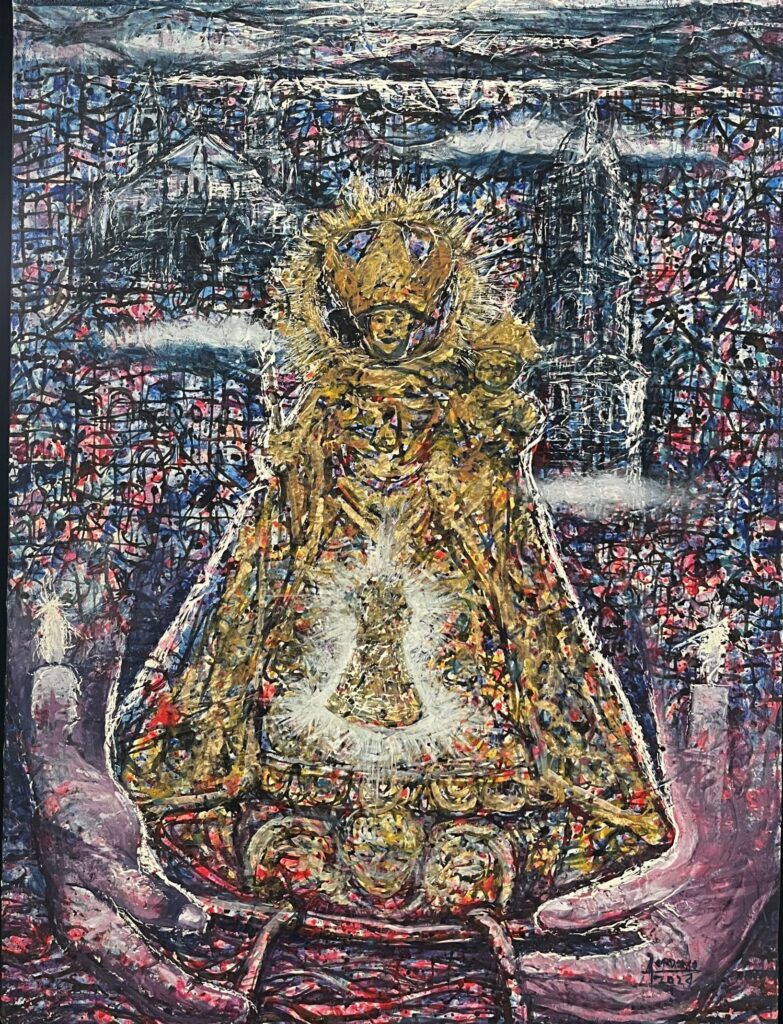

On collective devotion and, possibly, individual testimonies of miracles from such expressions of faith, we have Ordoyo’s portrayal of the Nuestra Senora de la Candelaria de Jaro. While it is true that the dominant Roman Catholic faith in the country is a result of more than three centuries of colonial experience under Spain, we often discount how much “input” our ancestors in the past and ourselves in the present have had on the practice of this Judeo-Christian/Abrahamic faith brought by Spain in the 16th century. Beyond its roots from the Marian cult and veneration in Europe, as with the “Infant Jesus,” lies “the story(ies) of the Candelara” from the memories and experiences of its earliest native devotees. From its discovery by fishermen at the river to accounts of its growth over the years, these narratives are reflections of how we made sense of or imagined the sacred icon; an indigenous imagination, so to speak, of the Christian faith. Going back to the creative work of Ordoyo, we can say that such inspiration can be rooted in one’s familiarity or connection with the subject. As such, an Ilonggo living in his/her own lifeworld as a Pentacosal Protestant/Born-again would not dare to imagine this, not unless he/she learns to appreciate its cultural and historical significance.

At times, these “tayog-tayog” stories, like those of the aswang, were used as a deterrent to keep children from going out at night. However, the imagined creatures that lurk in the dark can sometimes have parallels in real life. Such is Sarte’s depiction of the monsters and ghosts in both Filipino folklore and popular culture through a strong poster-like style reminiscent of the social-realist murals of the 1980s. The eyes of most of these nightcrawlers and ghouls face you upfront while some peak through the cracks with malicious intent. More than the apparitions that we imagine while listening to the aswang stories of our elders, these tales carry on a level of truth in the dark narrow alleys of major cities and in their victims whose blood-drained bodies have come to frequent our television sets since 2016. The victims are, as the title says, la familia indio – the poor Filipino family who is figuratively “crucified” for life or, in some cases, literally blindfolded with rags before execution.

“Tigbaliw,” by Jucar, would also fit in this narrative built on our familiarity with the creatures of folklore and urban myths. While the tigbaliw is generally known as a shapeshifter, Jucar’s sculpture is a monster standing on a pool of blood and bones – most likely the victims he had devoured – while casually holding a lit tobacco. The body’s built expresses greed and gluttony while its pointed finger on one hand and tobacco on the other emanates power. For any Filipino who is feeling the brunt of inflation and economic crisis, it is quite obvious as to who or what group of people this “tigbaliw” is imagined to represent.

Imaginings curated by new bodies of knowledge

While the stories of the aswang and that of the Candelaria also come from a body of knowledge, that is, it constitutes certain discourse of knowable symbols, icons, words, and shared meanings; they nevertheless can be defined as part of what historian Reynaldo Ileto calls, the “Little Tradition.” Most are learned through socialization in the family and through participation in collective rites and rituals. The next few pieces from the exhibit however, I would argue, are imaginings that are influenced by new knowledge acquired from educational institutions, books, conferences, interest groups, and artistic circles. What interests me is that these imaginings or attempts to portray what “tayog-tayog” is comes from places of either power or resistance to power. Of course, they are personal takes on a specific subject and they are as unique as those mentioned earlier but it is still important to examine the origin of what they have come to know and imagine.

Take for instance the works of Mia Reyes, Grapes Sevillo, and Larry Vido that draw inspiration from the Hinilawud or the Sugidanon epic cycle of the tumandok or Panay Bukidnon communities along the Central Panay mountain range. The oral traditions of the IP group would figure in strongly together with rural lowland folktales as they are learned and transmitted orally either as a pastime, as entertainment, or a lullaby to children at night. Also take note that these narratives and imaginings of heroes, ancestors, talking animals, and other creatures that inhabit the multi-layered realms of Panay Bukidnon cosmology come from a historically “othered” and socially marginalized people. Its entry into the stage of contemporary Philippine art, theater, nationalist projects, and in the process of identity-making of present-day municipalities whose political jurisdiction happens to include the ancestral domain of these communities is owed to the scholarship and publications of F. Landa Jocano in the late 1950s and, later in the 1990s, by Dr. Alicia P. Magos.

Reyes’ digital prints “Nagmalitong Yawa,” Tulogmatian,” and “Babaylan” gives a fresh representation of characters in the Panay epic and the babaylan in pre-colonial society through her modern comics-style illustrations and use of dialogues paraphrased and translated from the published books of the epics. Sevillo’s “Fading Time” is a simple yet timely commentary on the slowly vanishing tradition in the hinterlands due to modernization and lack of interest among the younger generation. Fortunately enough, there exists a number of SLTs (School for Living Traditions) that hope to retain this heritage cycle. Vido’s “Tayog-Tayog” which is also a modern take on the characters is highly relatable to a younger audience and is reminiscent of earlier folk and indigenous adaptations in visual arts and film animation. Their works are all laudable in their intention to adapt indigenous narratives and elements.

Now, we must continue with an interrogation of this series of (re)imaginings. We might ask, are they part of the Ilonggo imagination? Yes, but only to a certain extent. We have tumandok communities in all four provinces of Panay Island – provinces in the literal sense that they are politico-administrative units with territorial boundaries drawn and imagined on a map. The indigenous communities, however, care for little about these political boundaries as they cross over the mountains freely and maintain kinship ties across borders. As for identity, have we really taken the time to ask them if they see themselves as Ilonggo, Antiqueno, Akeañon, or Capiznon? Such questions must be addressed if we are to claim what is theirs as also ours.

In terms of reconstructing the clothing and ornaments of the tumandok and their heroes, we can only go as far as our primary sources allow us (if we are striving for authenticity). How should we paint their clothes? Should we base it on the present-day panubok designs? Should we limit ourselves to the samples from the Jocano collections? Or maybe we ought to revisit early Spanish accounts like Miguel de Loarca’s Relacion or the famous Boxer Codex and its Sino-European illustrations of the Bisayans? In many instances we commit the mistake of confusing and equating the indigenous to the precolonial — a tendency that I hope we can outgrow. We see this very often in murals and posters commissioned by LGUs or by some interest group where the Panay Bukidnon (or any IP group for that matter) is fitted into the backdrop of the precolonial past. All in all, the epic traditions are rich ground for young creatives to draw inspiration from and they should utilize these existing literature; but it is also a sensitive area that requires creatives to do some research, to be aware of the histories of the inarticulate and, if possible, to collaborate with the IPs themselves.

Still on imaginings from new sources of knowledge but now directly confronting the theme of colonialism, we have Juntado’s “Adventures of the Atomic Dwende.” One can see that his creative process has involved some reading of nationalist history and precolonial society. A dialectic is formed in the piece – on the right is the babaylan, a female (or who knows, this may be a male transvestite) and her spirit friend/guide, both of whom represent the precolonial world and its animist nature; and on the left is a Spanish conquistador and a small friar with a torch who represent the colonizer from the “Old World.”

From this “first encounter” we can see why it is the babaylan who is being confronted and not the datu. It is not so much because she is a woman or takes on being a woman but more so because she plays a central role in the spiritual affairs of the barangay as an intermediary between the realm of men and the realm of the unseen; and in precolonial societies almost every aspect of life has a spiritual element, be it in birth, marriage, raiding, planting, harvesting, etc. So, to consolidate power, the colonizer must cast away the babaylan and replace her with a new spiritual head (here it is the friar with the torch who has already burned a number of tao-tao behind him). Far more interesting are the creatures that accompany the conquistador, especially the one with the morion helmet and the liturgical headdress. It is an effective representation of the relationship of the Spanish crown and the (Spanish) Catholic Church of the Indies, which is manifested in the institution of the patronato real.

While this take is explicitly anti-clerical and anti-colonial, we ought not dwell in a sense of nostalgia for the precolonial past and in the many “what ifs” had the Iberians not come to our shores. History is not black and white, for if we look at our practice of the Catholic faith, can we really say that the friar missions have completely triumphed over the babaylan and her spirit friend? I do not believe so.

Perspectives on home and transcendence

Among those whose sense of “tayog-tayog” is more personal, Deya Java’s “Where the heart is” and Jecko Magallon’s “Holy Shiffft!” are the most playful when it comes to symbolisms. Java presents that the concept of home is never fixed to any place or structure; rather, it is a feeling of comfort and familiarity, it is “where the heart is.” Our first home is the womb, as the unborn are sometimes referred to as the “fruit of love,” and like the womb we grow up in the house (granted she has had good experiences in the house) whose every nook and cranny has become all too familiar and, subsequently, comforting. The grills of the windows of the common bungalow house in the country are placed in relation to the woman’s womb. Its curvature and protective function can be read as representative of motherly care and sense of security. Although for some, a sense of home can be attached to a person, a group, or a practice, making “the home” translocal.

On the other hand, Jecko’s “Holy Shiffft!” offers a symmetric and somewhat psychedelic interpretation of “tayog-tayog” or “out of this world” (while maintaining his distinct cubist style) by introducing the concept of transcendence. He plays with the alien and flying saucer that is about to transport a human figure and the large set of eyes over the figure’s head. Young artists tend to be part of one or two countercultures in the city, most of whom are welcoming of the re-emergence of Eastern Philosophies. In cosmopolitan centers many are starting to value peace of mind and transcendence over bodily pleasure and its by-product which is suffering. How such transcendence is achieved varies – from meditation, fasting, exercise, to using hallucinogenic substances. To the conservative whose life world is that of accumulation and consumerism, such personal choice truly is “tayog-tayog.”

To end, the exhibit’s celebration of “tayog-tayog” and surrealism has opened up many fruitful discussions and, most importantly, questions. Questions on Ilonggo identity and the sources of the Ilonggo imagination have been raised. We have seen that no creative piece emerges out of a vacuum; it always comes from a certain position, a certain history, be it personal or collective. It is also my belief that having this “tayog-tayog” mind is healthy as it makes us question things. Having an inquisitive mind, this is perhaps what makes the artist and the social scientist similar to each other, in that they appreciate the hidden workings of things in society and offer different explanations and readings, knowing that society, like history, is never black and white. However, the social scientist is constrained by his/her data, while the artist is required to be as “tayog-tayog”as possible – a license that he/she must optimize for noble purposes.