Infused with their own histories

In textile art, to look at the textile as a mere canvas devoid of intrinsic meaning is to disregard its history and discursivity. One therefore cannot read the works in “Intertextile” through a formalist point of view – detaching the artist from the work or looking at the work ‘as it is’ – for as the title of the exhibit suggests, these textiles have a nature of intertextuality. The fabrics are infused with their own histories and meanings which in turn are re-appropriated by the artists who are themselves shaped by their own lived experiences and ideologies. In this artistic process, the artist and the textile are engaged in discourse; the textile is not a passive element nor is the artist the only source of meaning.

The works from the Green Papaya Art Project’s archive shown in “Intertextile” (held at the Papaya xLAB from 26 February to 12 March) highlight the relationships between the textiles and artists; in that they are all produced by discourses on Philippine history, (cultural) anthropology, capitalism, gender relations, and the effects of time. To prove a point, the exhibit, by not giving emphasis on how all the works are by female artists, already engages in one of the discourses mentioned above; showing how certain explicit assertions have the tendency to further reify established relations of power among sexes. This is also the same reason why we ought to strive for a society that does not romanticize male decency or treat empowered women as exceptions to the rule.

Lived time and alienation

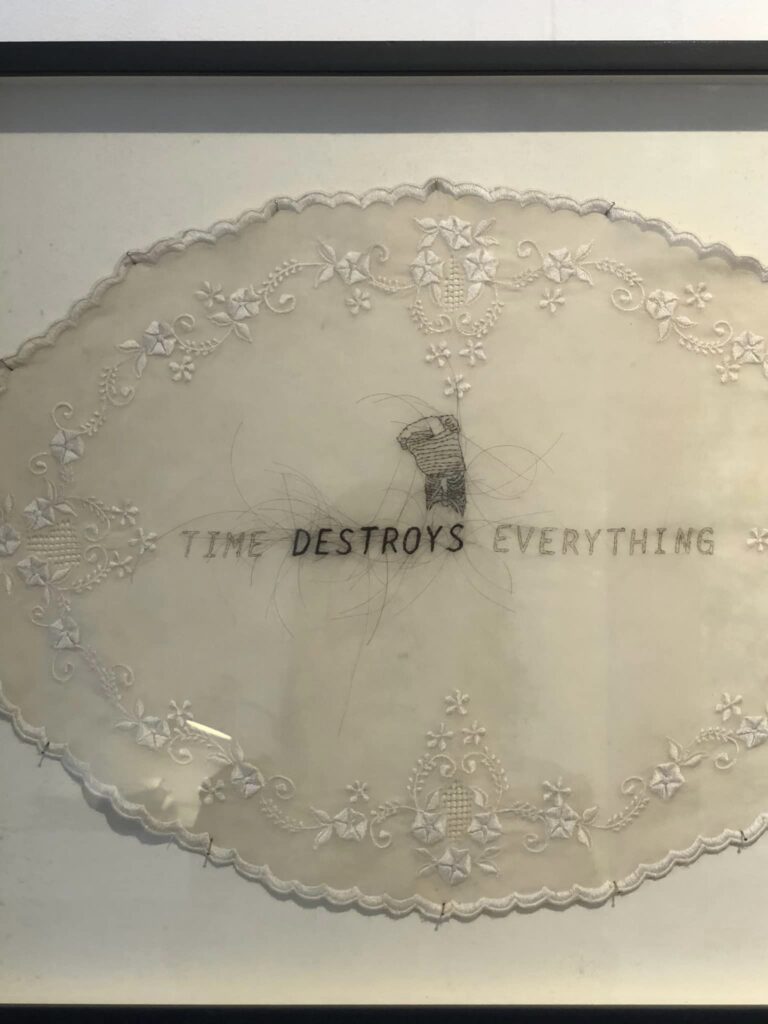

A section of the exhibit touches on the concept of temporality or the subjective perception of time. However, while messages of the textile communicate temporality, specifically the temporality of beauty and inevitability of death, a biomedical (scientific) dimension is added through the chemical processes (e.g. natural or induced rusting, bleaching, natural dyeing, etc.) that allow these narratives to manifest in the textile. Time Destroys Everything by Lara de los Reyes exemplifies this merging of the phenomenological and the medical with the use of her own hair as embroidery on a vintage doily tablecloth. The discoloration of the vintage doily and the symbolic use of human hair to embroider the text and the figure of a person removing a shirt (which exposes the skeleton) both involve chemical processes that show the deteriorating effects of time – the rusting of the doily (oxidation) and decomposition of the human body wherein the hair, along with the bones are what remains. Giah de los Reyes’ Sa Paglugom sang Damgo also works with such chemical processes. Her assemblage of hanging fabrics that are bleached, rusted, and treated with natural dyes not only challenges the notion of framing textile art but also expresses how the (chemical) processes involved in inducing changes to the textile are themselves essential components of the art. Furthermore, the process is not only chemical but also historical, since the practice of applying natural dyes (with natural mordant like lime) to textiles is deeply entrenched in the cultural history of the region from where she hails.

It’s trash till there’s a minder by Kat Medina likewise relates to lived time, but her use of industrial embroidery on commercial textile samplers redirects us toward the history of the object as a product of the ‘assembly line’. It is an object whose medieval and tribal motifs have been taken out of context and has lost their meaning after being incorporated into the aesthetics of a product that is mass-produced by machinery – machinery that is in turn operated by workers who are themselves alienated from their work. Adding to this layer of alienation and capitalist indifference are the conspicuous tags which contain barcodes and other details of the commodity. However, although barely visible, there are rumblings and murmurs of dissent against this dehumanizing system in the form of the embroidered phrases “casual pain” and “subtle pressure”.

Gender and history

The connection between the ability of textile and embroidery to convey narratives and the long history of women in the region as weavers of a people’s identity and storytellers of their history cannot be denied in the works in “Intertextile”. This is most prevalent in Lesley-Anne Cao’s Thread which explores, through text and textile, how norms on sexuality and ideals on beauty are translated into the way clothes are perceived. Also on the potential of textiles in becoming narrative tools is Con Cabrera’s re-rendering of the now popular zine (a small circulation publication that is usually photocopied) by using thread drawings and fiber fill in her Telex Moon Soft Zine. Meanwhile, narratives on our history of anti-colonial struggle and its millenarian nature clearly pervade Tekla Tamoria’s embroideries on hand-sewn amulet (anting-anting) vests, as it links the rural folk’s understanding of Catholicism and persistence of babaylanism (a tradition once dominated by women and male transvestites) in their understanding of revolution.

Textiles as battlefield

Tamoria’s explicit message on millenarian movements relates with those of Olive Gloria and Margaux Blas whose assemblages of fabric, text, and symbols become an open field for both negotiation and resistance. Gloria’s We Don’t Realize How Enslaved We Are to the Pressure Ordinary combines indigenous needlework, vintage images, and commercial patches to tackle the politics of remembering, particularly how we remember our colonial experience under the United States. The commercial patches and love letters written in English can be likened to our fabricated relationship of unity, partnership, and love with America even after independence which was fostered by decades of colonial education and cultural hegemony. As with the vintage images made vague by layers of vibrant color, so too does something much sinister lie behind this whitewashed history.

On the other hand, Junior Lapad by Blas reflects the blurring of lines between the sacred and the profane, a negotiation between these opposing elements that are often overlooked in how we perceive the psyche and worldview of the rural folk. Both the sacred (the cross) and profane (Tanduay rum) are constant scenes in the daily life of the barrios. By reimagining the façade of a Spanish-era church as the contours of the junior lapad and with the iconic ‘T’ of the liquor brand serving as the central crucifix, the meanings attached to practices that would otherwise be in complete contradiction to each other are seen here to intertwine into a particular way of seeing the world. Devotion to Christ and the Saints (through prayer and rituals), as with the drinking of lapad (which has its own rituals), is an almost daily affair (adlaw-adlaw). Blessings and prosperity, as shown by an outpouring at the top of the church/lapad are also celebrated through praise and, once again, a toast and shot of Tanduay rum with one’s kinsmen. Overall, its merging is reflective of how people cope with hardships, as well as in how they collectively celebrate prosperity (e.g. good harvest, favorable weather, etc.) and milestones (e.g. Christenings, weddings, fiestas, etc.) in community life. Bugana is always poured over.

Intertextuality

Through these works on textiles, the artists in “Intertextual” are bound by the power of the medium they use and by their appropriation of these materials, which are already heavily laden with histories of their own, to narrate hidden/suppressed stories and oppose dominant discourses (such as on gender and colonialism). By embracing the history, origin, and context of the textiles and their related processes (i.e. weaving, embroidery, natural dyeing, bleaching), the artists have made them not just as canvas but as text to convey narratives and as a field for the negotiation of meanings.