Language is an interesting thing; the same word can mean two different things in diverse dialects.

Ginoe’s “Banal Banal” or “Sacred Ordinary” explores that very concept by meeting two seemingly polar opposites and making them far more similar to one another than what originally meets the eye.

“I’ve heard a lot of stories when I was younger not surprisingly there are no images to accompany them, photographs or even illustrated histories because the Philippines is notorious for oral histories. So in this one, I tried to harvest as many stories as I can and as many that relate to religion or something biblical and to make images that anchor them so that they don’t disappear. Occasionally, oral stories either disappear or evolve into another story that isn’t connected to the first story. “

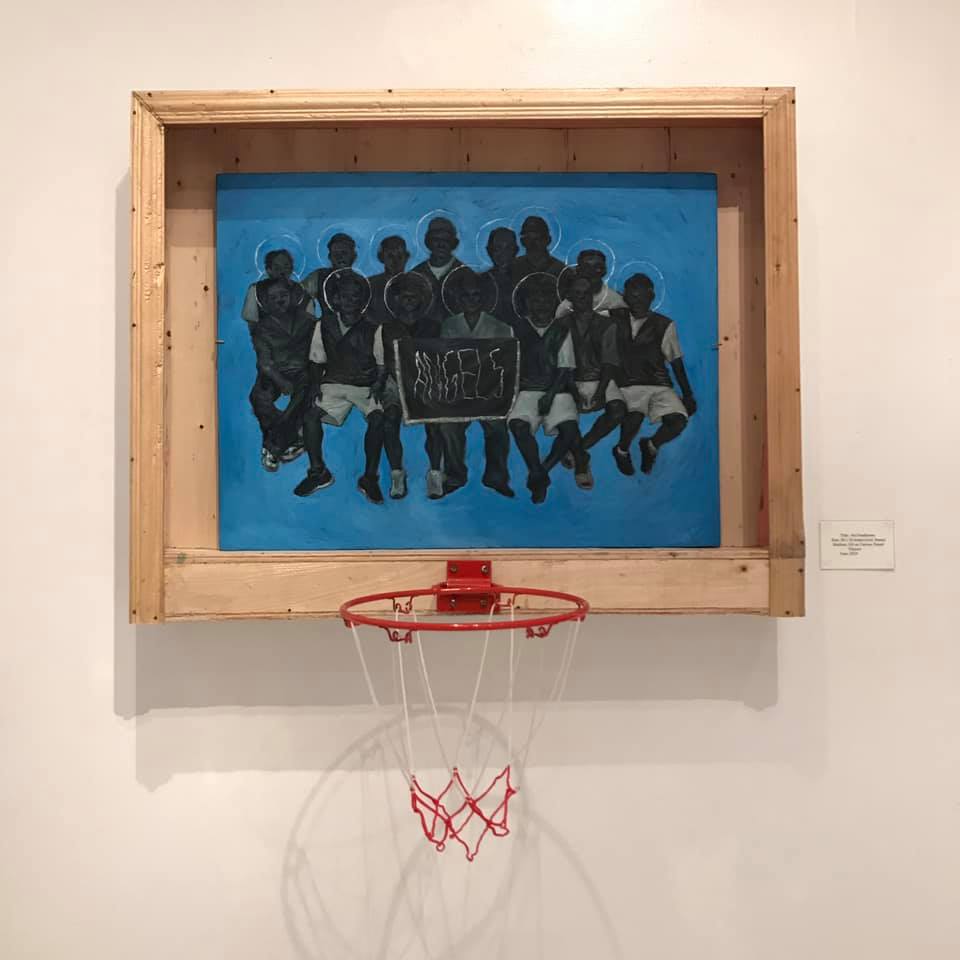

“I have a story about the basketball image but when you take it as an image it looks like the Last Supper, like a tableau. The burning coconut tree is like the burning bush from the Bible. The basketball ring was supposed to be fishnet and to be placed with crosses kind of like a river; my community is a fishing community. I’m not disrespecting biblical stories, I’m referencing them because in a way the life of common people can also be spectacular and should be recorded.”

According to the artist, religious images are usually only reserved for old characters like Joan of Arc who was a knight and whose image has been glorified.

In this way, Ginoe reached out and found elements from his community and revered them to the level of grandiosity religious imagery has. An example is his installment of twenty-four banderitas featuring St. Joseph the Worker, who was originally a carpenter but Ginoe turned him into a sacada. In doing this he localized the image which was also a tribute to laborers who were killed. Behind the image of St. Joseph is an English prayer that he translated to Spanish that adds a level of encryption to the work. The artist used chains to hang the banderitas as a critique on unfair labor practices which is a kind of slavery.

Directly opposite the wall with the banderitas installation stands three Sto. Niños who look as though they’re being pierced by glass shards. This piece is in reference to the local practice of using broken pieces of glass on their gates to ward off theft. “The start of that series is to denote pain when they proposed to lower the age of criminality in the Philippines, to me, that’s an attack on childhood. I think Sto. Niño as an image is a nice arena to tackle issues about children and the youth because he’s like the prime child. It’s the child image of Jesus Christ but at the same time, it exists as a major entity on its own in the Philippines. There’s a difference between the Child Christ and Jesus on the cross, but they’re the same person.”

‘There is a reverence for innocence about youth in the Philippines but at the same time on the flip side why did they lower the age of criminality? Why are there children getting murdered in the drug war? This is a good image to interrogate ideas because of the familiarity of youthfulness and being a child. It’s not out of blasphemy or disrespect, it’s out of me trying to test what the extent of someone as a Filipino Catholic, can accept that it’s Sto. Niño you’re mutilating. I can’t help but think of the murderous edict by King Harod who ordered the killing of infants simply on the prophecy that one would rise to overthrow him as king of Judea. I want to make people question their stances especially if it’s issues about children in the Philippines.”

Perhaps the most revelatory thing about this show is how close to home and heart the artist has made it. “The people I drew from don’t have access to a gallery. So it’s like me acknowledging that I took it and brought it here, that’s the act of it.” He says as the conversation moves onto his choice of framing. “You can see the nails and pencil marks, it’s very crude. I wanted to capture the mood of a makeshift altar of an impoverished community. Like in our place, even the coffins are made by the people themselves because it’s cheaper. I don’t want to sanitize the images, I want them to have the proper context. The holy sites in our area are made of cheap wood and things, but it doesn’t make them less holy.” Ginoe worked hard to represent his narrative in as clear a light as possible, trying his best not to condescendingly glamorize the hard work of people from lower-income areas.

“I think art doesn’t exist in a vacuum but I think it exists in a place that part of it is not in the realm of the waking life. That’s why it’s important. It’s not that you’re alienating your viewers. It has to have context. Works that are in a gallery come from somewhere and I want that somewhere to reflect in the work while it’s in the gallery.”

Note: Ginoe’s “Banal Banal” was shown at the Kapitana Gallery last August 2019.